Chapter 1: Chair Massage Techniques

Chair massage, also referred to as seated or onsite massage, is described as bodywork treatments given to a clothed individual while in a seated position. With the chair’s unique features, it enables the client to lean forward in an upright, semi-prone position while resting their face on a cushioned face cradle. Additional padding attaches to the chair’s structure to comfortably support the client’s arms and legs. Most massage chairs today are equipped with easy adjustment mechanisms to accommodate various body sizes for proper positioning before each session.

Not only does chair massage enable the therapist to focus on high tension areas of the neck, shoulders, and back region, but various techniques can also be performed on the upper chest, scalp, arms, hands, and even the legs and feet. Sessions generally last anywhere from 5 to 30 minutes or longer, with the average being 10 to 15 minutes. Seated massage does not require the use of lubricant during treatments; however, some therapists may apply lotion when working on the client’s posterior neck or their arms and hands. Depending on the set-up and location, a lubricant is often applied to the client’s feet during a foot massage treatment. Keep in mind that even though many clients prefer to have some lubricant, others may have skin allergies to specific products or may not like the idea of feeling greasy afterward or risk getting it on their clothes. Therefore, it is always best to ask permission before performing any techniques.

Chair massage generally only uses a few basic techniques, but many bodywork professionals utilize other modalities or classify strokes under different names. Even though the methods themselves are administered in the same way, the therapist determines the approach according to their client’s needs. Swedish massage is perhaps the most common form of bodywork used in seated massage. It is characterized by the use of five basic strokes: effleurage, petrissage, friction, vibration, and tapotement. These techniques are used to relieve physical and emotional stress, improve circulation, increase flexibility, facilitate the removal of toxins, and encourage the healing of soft tissues. The following section provides a brief overview of Swedish massage and several other techniques performed during chair massage as well as body positioning and areas of the body that warrant caution.

Effleurage

Effleurage stems from the French word effleurer, meaning “to touch lightly” or “stroke gently.” Effleurage consists of long, soothing, gliding strokes applied by the palms of both hands (Figure 1-1). This technique is often used at the beginning of each session to warm up the tissues and also at the end for a relaxing finish. An important rule with effleurage is to implement movement in the direction towards the heart. The depth of pressure may change between the outward movement and the return stroke, generally, with more force applied towards the heart, then slightly less in the return action, and so forth, repeating the sequence.

Petrissage

Petrissage arises from the French word patrir, meaning “to knead.” It is a technique used to manipulate the underlying tissues by applying a push-pull or grab-release movement using the palms, fingers, and thumbs while alternating the hands in a rhythmic motion (Figure 1-2). Ringing and skin rolling are forms of petrissage used to lift soft tissues away from structures to help relieve tension, loosen muscles fibers, increase blood flow, and stimulate lymphatic responses.

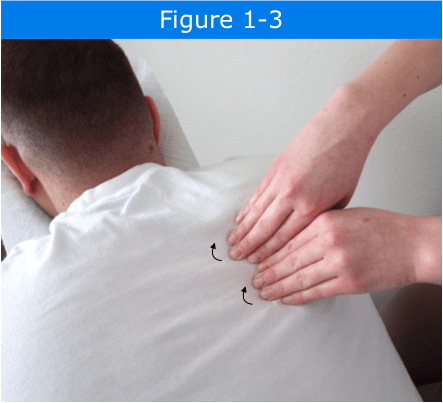

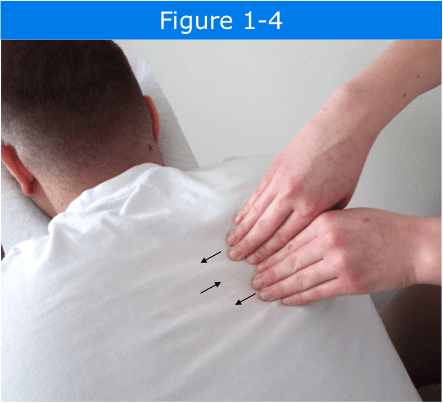

Friction

Friction originates from the Latin word frictio, meaning “to rub” or “rub down.” Friction is best performed by pressing on the soft tissues rather than gliding over the top of the client’s skin to work deeper structures. Circular friction is applied just directly over the underlying tissue(s) of focus by using either your thumb pads, palms of hands, soft fists (knuckles), or fingertips in a circular motion (Figure 1-3). Transverse friction, also known as cross-friction or cross-fiber friction, is a movement performed across, or in a back and forth from side to side motion (Figure 1-4). Often the forearm or elbow is used if additional pressure is needed.

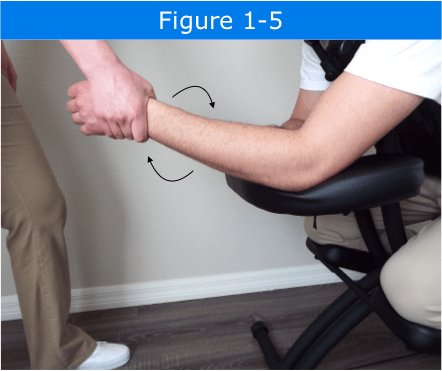

Vibration

Vibration is a technique that involves shaking, rocking or jolting. The therapist places their fingertips or palms on a muscle and shakes it sufficiently only to provide enough movement to the tissue(s). When applied firmly, one or both hands are used to grasp the body region, then rapidly shake the muscle for several seconds (Figure 1-5).

Tapotement

Tapotement is part of the French word “Tapoter,” meaning to tap, pat, or drum. In massage, this technique is also referred to as percussion. Both are categorized as a group of repetitive rhythmic movements used to stimulate the nervous and circulatory system. Some types of tapotement techniques include:

- Pounding is performed by positioning your hands into loosely clenched fists and then gently striking the client’s body in an alternating movement (Figure 1-6).

- Hacking is applied using the outer edge of both hands (ulnar side) with loose wrists that strike the client’s body in a fast, chopping rhythmic motion (Figure 1-7).

- Cupping is performed with the palm side of each hand formed into the shape of a “cup,” then lightly striking the client’s body in an alternating motion (Figure 1-8).

- Plucking is used to gently touch the client’s skin in a light pinching or pecking movement (Figure 1-9).

- Tapping is performed using relaxed fingers that tap the client’s tissues with intensity producing a slightly hollow sound (Figure 1-10).

Additional Massage Techniques

Additional techniques performed during a chair massage session may include compressions, brushstrokes, elbow work, deep tissue, and various stretching methods. However, therapists will often modify specific techniques or approach another modality differently.

Compression

Compression is another technique often used to introduce the therapist’s touch to a client, as well as bring blood flow to the surface, and prepare the muscles for more sustained pressure. Many massage therapists use this technique in combination with other methods. To perform compressions, place the palms of both hands over the muscle(s) being worked, then gently press down in a slow pumping motion, and release (Figure 1-11).

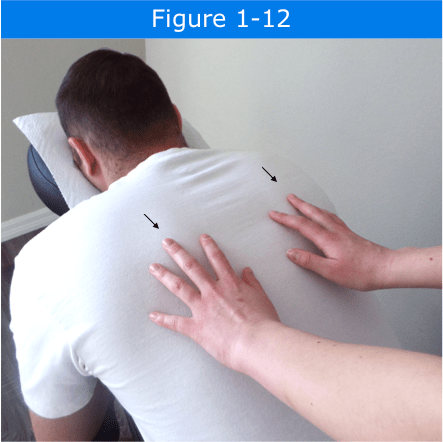

Brushstroke

Brushstrokes are also referred to as “feather strokes,” for its lightness of touch. Therapists use their fingertips to perform a soft gliding motion simultaneously in the same direction or an alternating movement when ending a session (Figure 1-12). Keep in mind that many clients are ticklish and may need the pressure adjusted so that it does not disrupt their treatment.

Elbow Work

Elbow work is used to apply deep pressure to address underlying tissue layers. Before performing elbow work, therapists should first palpate the area to ensure the elbow is placed on the muscle and not on any bony landmarks or endangerment sites. Once located, support your flexed elbow in place and gently lean in to apply sustained pressure on the tissues of focus then slowly release (Figure 1-13).

Deep Tissue

Deep tissue massage is designed to manipulate the deepest layers of muscles, tendons, fascia, and other structures. The term “deep tissue” is often misused and is a separate form of massage used to treat specific musculoskeletal disorders. Deep tissue should not be confused with “deep pressure” massage, which is performed with more intense sustained pressure throughout a session. Deep tissue techniques require advanced training and it is not recommended for clients with sensitive skin or those who have a low tolerance to firm pressure. Also, it is important to know that some clients may develop bruising after a deep tissue massage or develop other side effects.

Stretching

Stretching techniques consist of pulling a body region or extremity away from its neutral position within a specific muscle or muscle group. The goal of stretching is to gain flexibility and restore normal range of motion. To achieve the effectiveness of a stretch, the therapist must first understand body movement and be aware of any tissue restrictions or potential contraindications. Furthermore, therapists should always modify each technique accordingly and allow the client to verbalize their limits, and never apply sudden, forced movements to increase their range of motion. Although therapists will only perform specific stretching techniques to clients in a seated position (demonstrated in Chapter 2), they can, however, recommend alternative methods for further assistance.

Breathing Pattern

Breathing is one of the few bodily functions that can be either voluntary or involuntary. Because of this unique function, therapists can utilize specific breathing patterns that will help the body to relax when performing treatments to their clients. For example, when applying pressure, both the therapist and client must use a breathing pattern by exhaling out the mouth when applying pressure and inhaling through the nose when the pressure is released. By breathing in enough oxygen, it puts the body in parasympathetic mode and helps the therapist to remain focused and the client to feel more relaxed throughout the session.

There are two main types of breathing techniques: chest and diaphragmatic breathing. Chest breathing (or shallow) is the process of drawing minimal air into the lungs by using the chest muscles rather than throughout the lungs via the diaphragm. This type of breathing tends to be short and quick, using only a small portion of the lungs and delivering a relatively minimal amount of oxygen into the bloodstream. Diaphragmatic breathing, also known as deep, stomach, or abdominal breathing, is the most common form of breathing used in massage therapy for stress reduction and relaxation. The diaphragm is a muscle that separates the chest cavity from the abdomen, and it is the primary muscle in respiration. As the diaphragm expands, it enlarges the chest cavity, allowing for more air to flow into the lungs. Breaths taken are usually slow, deep, and deliver a significantly larger amount of oxygen to the bloodstream.

Other Modalities

Although there are numerous massage modalities currently performed in the massage and bodywork industry today, below are just a few examples of different methods that can be utilized during a chair massage session.

| ACUPRESSURE – is a technique that uses finger pressure on assigned points located on the body to relieve pain, create anesthesia, and regulate body function. |

| AROMATHERAPY – is the use of various oils from plants that can either be absorbed through the skin or by inhalation. Specific herbs are thought to help heal the body and react in areas of the brain that are related to emotions and past experiences. |

| MYOFASCIAL RELEASE – is a type of soft tissue therapy used to treat skeletal muscle immobility and pain caused by chronic tension and myofascial restriction. |

| REFLEXOLOGY – is the application of applied pressure to specific points on the feet, hands, or ears that correspond to other regions throughout the body. By pressing on these points, it stimulates the nervous system and opens energy pathways that may be blocked or congested. |

| REIKI – is a visualization and a “no-touch” “hands-on” technique to improve the flow of life energy and alleviate conditions on an emotional, physical, and spiritual level. |

| SHIATSU – is a Japanese method of acupressure, in which pressure is applied by the thumb, elbow, or knee, at precise points on the body in combination with the rotation of joints, kneading, and various stretching techniques. |

| SPORTS MASSAGE – is a systematic manipulation of the soft tissues relevant to a particular sport. It is designed to aid in pre/post athletic performance to minimize sports injuries by alleviating muscle tension and inflammation. |

| TRIGGER POINT THERAPY – is the use of ischemic compression within a specific location of hypersensitivity in a tissue to alleviate the source of pain in other regions of the body. |

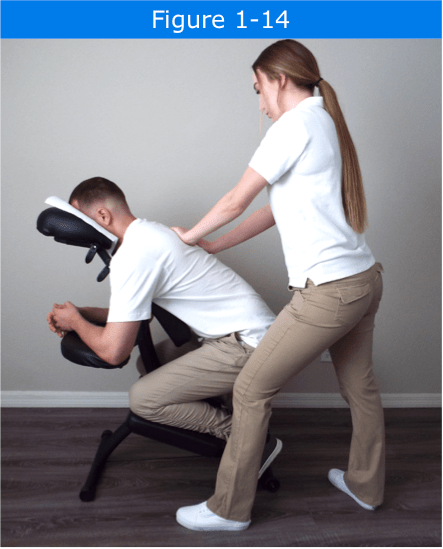

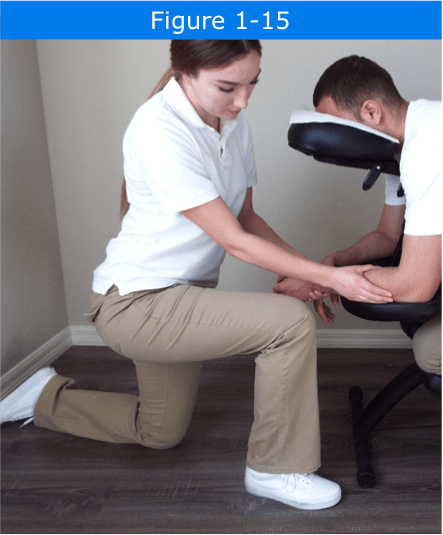

Body Positioning

In massage therapy, body positioning, or otherwise known as stance, is an important part of being able to perform bodywork techniques safely and effectively. Stance is how the body is supported when someone stands. It generally involves placement and/or movement of the legs, feet, hips, arms, and the head. Although body mechanics will vary depending on the specific working conditions, the two most commonly used stances in massage therapy are the lunge stance and the straight stance.

The lunge stance is also referred to as the archer stance or bow stance. In this position, the back is straight, legs are hip-width apart, one foot is stepped forward in front of the other, and the front knee slightly flexed (Figure 1-14). Most of the bodyweight will come from the therapist’s rearfoot and strength administered from their back leg when applying pressure. The amount of force is controlled by shifting forward when executing movement and releasing pressure on the backward movement, generating a rhythmic motion. In chair massage, therapists will often perform what is known as a lower lunge stance, or kneeling stance when addressing the client’s arms, lumbar region, and the legs (Figure 1-15). If accessible, you can choose to use a stool, or chair, instead of kneeling. The straight stance is also known as the horse stance or warrior stance. In this position, the back is straight, and the feet are shoulder-width apart (Figure 1-16). The weight should be evenly distributed between each leg and the pelvis balanced so that it can shift from side to side without restriction, creating a rocking motion when applying techniques.

Areas of the Body that Warrant Caution

Contraindications

As part of the assessment before performing bodywork treatments, therapists must give their full attention to any questions or health concerns that a client presents that may or may not be a contraindication for treatment. For massage professionals, a contraindication is any condition, specific symptom, or factor that would prohibit a treatment from being administered due to the harm it may cause the client or the therapist. A contraindication can be considered either a local or an absolute contraindication. Local contraindications, sometimes referred to as partial, implies that the massage therapist must exercise caution and avoid working directly within a region while modifying techniques accordingly. Absolute contraindications, sometimes referred to as general, are situations in which a massage should be avoided entirely. Although not all conditions are completely contraindicated, it is imperative therapists obtain a physician’s medical approval before proceeding. By doing so, it will not only protect the client from harm, but it also protects the therapist from a potential lawsuit.

In chair massage, many conditions may not be immediately evident or visible to the therapist since the client is wearing clothing. Also, some clients may not even be aware of their condition or will avoid mentioning anything for fear of being denied treatment. If a therapist discovers or feels an unusual area of concern that is painful, sensitive, or could be harmful to the client or themselves, then it’s best to avoid the area and use thoughtful consideration before proceeding. Therapists should suggest the client contact their healthcare provider or refer them to a professional that is within their scope of practice to diagnose and treat a condition, complaint, or injury.

Remember, massage therapy does not constitute medical treatment and is not a substitution for a medical examination or diagnosis. Although therapists do not diagnose diseases, nor do they cure them, they can, however, provide healing benefits for specific conditions. When working with a client with a particular condition, you must be able to modify the treatment as needed or avoid the session altogether. If there is any uncertainty, then always side with caution and obtain medical authorization.

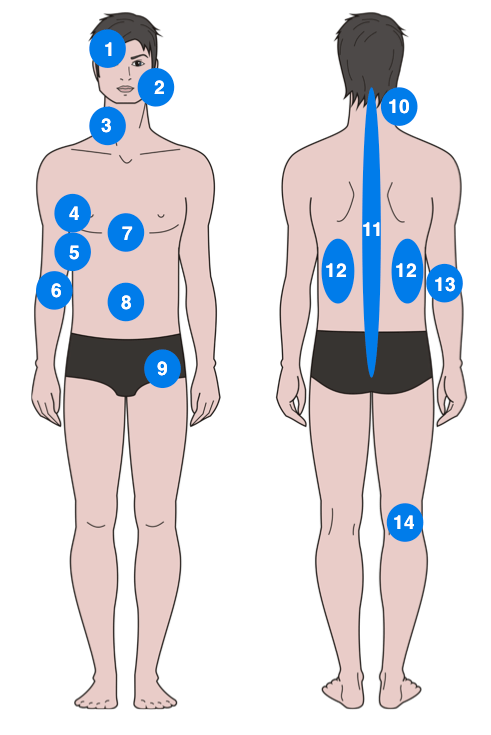

Endangerment Sites

Endangerment sites, sometimes referred to as cautionary sites, are areas of the body where delicate structures have little protection, such as blood vessels, nerves, organs, and bony prominences. Because of the limited protection, techniques performed in these regions warrant caution and often managed by adjusting pressure, modifying techniques, or avoiding the area altogether. These areas include:

- Temporal & forehead

- Inferior to the ear

- Anterior triangle of the neck

- Axilla

- Medial brachium

- Antecubital fossa

- Sternum

- Abdominal region

- Femoral triangle

- Posterior triangle of the neck

- Vertebral Column

- Low Back (kidneys & ribs T11 & T12)

- Olecranon process

- Popliteal

Therapists should always take the necessary precautions and refrain from any bodywork to areas that may cause injury or be dangerous to a client. When working around endangerment sites, you should use light pressure and avoid pressing directly over bones, nerves, or blood vessels, remember if you feel a pulse, move away. Direct pressure on an endangerment site can cause tissue damage, bone fractures, bruising, shooting pain, tingling, numbness, dizziness, and syncope (fainting).